telethon salon

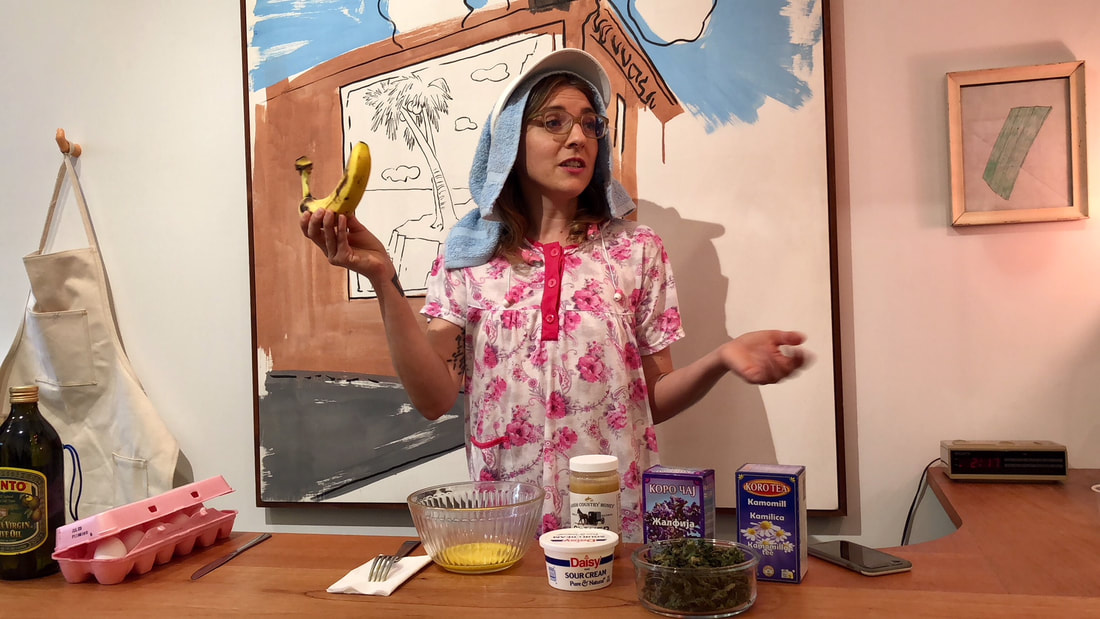

The following is an essay I wrote for the second issue of Pedestrian Magazine followed by a video of my performance at Capsule Gallery in NYC on June 16th, 2018:

I first met Dara on the street in Ridgewood, Queens in 2016. I was on my way to the laundromat. She was leaning on the metal gate outside my apartment wearing a long, black skirt and a navy blue, knit vest over a white blouse. Her gray and golden hair was wrapped up in a braided bun secured by a plastic headband with flexible teeth. The bun was draped in a black scarf and around the scarf, a matching black visor secured the hairstyle like a crown.

When I opened the door I was startled to see her. She was just a few feet away with a blue dolly full of plastic bags. She turned around and looked at me through her big glasses and said gently, “Hi Hohn-ey.” I smiled and said "hi".

Despite my surprise there was something comfortable about the exchange. I felt like I’d seen Dara before, as if we had planned this day and only upon seeing her did I vaguely remember. She explained she was waiting for her friend, Ronnie (NOT her boyfriend) to pick her up and bring her to his house so she could make dinner, her daily routine. Dara asked if I would come to her house and translate her mail sometime by reading it out loud. I obliged, and as a reward she gave me five pieces of cinnamon Trident chewing gum.

This transaction was the first of many which set precedent for my relationship with Dara. Since that day I have acquired an entire wardrobe as payment for translating letters and doing other household chores. For example, after I made arrangements with her doctor I received a pair of green sweatpants and a black skirt meant to be worn as an ensemble (Dara's orders). Also among my acquisitions are several knit dresses, khaki pants, earrings, a bottle of used nail polish, instant coffee, crackers, a bag of sunflower seeds, a tube of Nice ’n Easy hair conditioner, Jasmine flowers, apples, an Abercrombie and Fitch sweatshirt, and a special mask which Dara demonstrated on my hair when we had “beauty salon” one Sunday morning at her apartment. I also received a men's XL Mark Anthony Budweiser t-shirt that has armpit stains and a hot pink, sexy see-through nightgown. It confused me where Dara found the last two gifts.

Dara has lived in her second story apartment for thirty six years, ever since she moved to Ridgewood from Serbia. The living room is curated with shelves of plastic toys, tarot cards, stacks of magazines from Capital City, dolls, photographs, and ceramic candy dishes. Sometimes she reads to me from her magazines. She loves to talk about organ trafficking, one of her worst fears. She blames the Albanians and Hilary Clinton. She also told me someone once tried to throw her off a roof by luring her there to see tomato plants. Luckily Dara was not fooled.

In the apartment, two lace curtains tied with red ribbons provide a segue from the kitchen to the living room. The spare bedroom with blue wood paneling stores a fold-up bed though Dara sleeps in a chair in the living room. Since she lost her daughter a year ago, Dara keeps an altar in the periphery of the living room. Holy candles burn brightly around prayer cards and a portrait of Dara’s daughter who wears her hair like her mother: a braided bun wrapped neatly and coiled on top of her head, softly framing her demure smile.

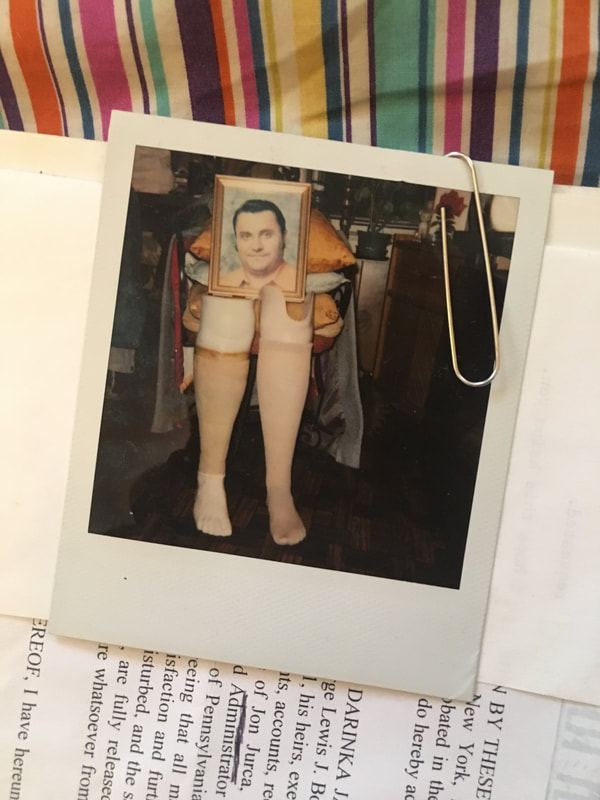

Also in the living room is a portrait of Dara’s friend, John, a double amputee. It is an old fashioned, color-corrected photo of a handsome guy with greaser hair, a crooked smile, and a collared shirt. Dara created a still-life by placing John's portrait on top of his two prosthetic legs. She took a polaroid of the arrangement and paperclipped it to a letter. Dara took care of John until he passed away, a similar relationship, it seems, to the one she has with Ronnie.

When I opened the door I was startled to see her. She was just a few feet away with a blue dolly full of plastic bags. She turned around and looked at me through her big glasses and said gently, “Hi Hohn-ey.” I smiled and said "hi".

Despite my surprise there was something comfortable about the exchange. I felt like I’d seen Dara before, as if we had planned this day and only upon seeing her did I vaguely remember. She explained she was waiting for her friend, Ronnie (NOT her boyfriend) to pick her up and bring her to his house so she could make dinner, her daily routine. Dara asked if I would come to her house and translate her mail sometime by reading it out loud. I obliged, and as a reward she gave me five pieces of cinnamon Trident chewing gum.

This transaction was the first of many which set precedent for my relationship with Dara. Since that day I have acquired an entire wardrobe as payment for translating letters and doing other household chores. For example, after I made arrangements with her doctor I received a pair of green sweatpants and a black skirt meant to be worn as an ensemble (Dara's orders). Also among my acquisitions are several knit dresses, khaki pants, earrings, a bottle of used nail polish, instant coffee, crackers, a bag of sunflower seeds, a tube of Nice ’n Easy hair conditioner, Jasmine flowers, apples, an Abercrombie and Fitch sweatshirt, and a special mask which Dara demonstrated on my hair when we had “beauty salon” one Sunday morning at her apartment. I also received a men's XL Mark Anthony Budweiser t-shirt that has armpit stains and a hot pink, sexy see-through nightgown. It confused me where Dara found the last two gifts.

Dara has lived in her second story apartment for thirty six years, ever since she moved to Ridgewood from Serbia. The living room is curated with shelves of plastic toys, tarot cards, stacks of magazines from Capital City, dolls, photographs, and ceramic candy dishes. Sometimes she reads to me from her magazines. She loves to talk about organ trafficking, one of her worst fears. She blames the Albanians and Hilary Clinton. She also told me someone once tried to throw her off a roof by luring her there to see tomato plants. Luckily Dara was not fooled.

In the apartment, two lace curtains tied with red ribbons provide a segue from the kitchen to the living room. The spare bedroom with blue wood paneling stores a fold-up bed though Dara sleeps in a chair in the living room. Since she lost her daughter a year ago, Dara keeps an altar in the periphery of the living room. Holy candles burn brightly around prayer cards and a portrait of Dara’s daughter who wears her hair like her mother: a braided bun wrapped neatly and coiled on top of her head, softly framing her demure smile.

Also in the living room is a portrait of Dara’s friend, John, a double amputee. It is an old fashioned, color-corrected photo of a handsome guy with greaser hair, a crooked smile, and a collared shirt. Dara created a still-life by placing John's portrait on top of his two prosthetic legs. She took a polaroid of the arrangement and paperclipped it to a letter. Dara took care of John until he passed away, a similar relationship, it seems, to the one she has with Ronnie.

Dara told me John spent the last days of his life in a small town in northeast Pennsylvania. Coincidentally this is close to where I grew up and even closer to where I have my trailer. When I told her this, Dara was excited because she had been wanting someone to go to the local bank and investigate where John's money went. This was the inheritance that Dara felt she was entitled to after John died. During a visit to the trailer I made an appointment with a consultant at PNC bank in Hazleton. Without any paperwork, and a long, baseless story, the bank teller was not convinced she should give me $10,000 for a friend. I thought maybe Dara could better explain first-hand on speakerphone-- after all she cooked a lot of dinners-- but even then, I left without a dime.

One day I was looking at the altar in Dara’s living room. I noticed the mugs that held the holy candles had writing on them. One of the mugs said “Chocolate is always the answer” and the other one said “Bacon is the reason I get up in the morning.” When I pointed and kind of laughed at the emotional discrepancy Dara asked, “How it says?” I felt bad explaining she accidentally included jokes in the memorial. The messages on the mugs sounded like iterations of things Dara might say. For example, when I brought her cough medicine once she said: “I robber to you tonight.” (She meant “I’m stealing from you.”) Or a few weeks ago when she told me her landlord never responded to her complaint about water on the roof: “He’s quiet like a fish.” When I asked what she meant she looked at me like I was an idiot and responded: “Fish don’t talk.”

From the moment we met on the street, Dara has lapsed between a person and a mysterious vision. I picture her black veil and long skirts, the way her cigarette smoke wafts around the lace curtains and Cabbage Patch Kids in her apartment. She eats cough drops and laments the loss of family members while we drink instant coffee that she boils with tons of cream and sugar in a small pan on the stove. Once when my allergies were bad, Dara held my head in her hands and poured cold chamomile tea into my eyes. Another time she scolded me for wearing sandals without socks, insisting it would destroy my ovaries. When I tried to hug her that day she recoiled to stress her point. (“How you make’a husband if no take care’a self?”) Recently she asked me to write a grievance to National Grid on her behalf. Dara orated her complaints which I wrote in her spiral notebook. I wasn’t sure if I should summarize her words, or if I was supposed to transcribe the statements directly, including: “You suck like snake to the life.” The language barrier is authentic but Dara knows she's a poet.